Articles and information about Splash and the work we do.

August 29, 2014

A Bitter Gift

Originally published in 2013

When I held my son, Liam, for the first time, he was two hours old, and the rest of the world disappeared. He and I were not alone: my wife, Susanna, was at our side; Liam’s birth mom was looking on (and would soon take our very first family portrait from her hospital bed); his birth dad was in the corner; and a social worker watched over her clipboard. I’m sure there were nurses. But for a moment all I knew were the alert little blue eyes, the smell of a newborn, the gentle rhythm of his miraculous breathing.

John Donne captured the sensation perfectly in one of his love poems, where he describes his beloved as an entire world, and himself as the only person in that world:

“Nothing else is.”

So simple. So sweeping. I had no thought for John Donne in the hospital that day, but I understood exactly what he meant by that line, and I still do.

What disappeared in that moment was not just the crowded hospital room, but also a long and excruciating adoption story that stretched across several continents and nearly four years.

We had finished all of the paperwork for a Chinese adoption when the process in that country slowed to a crawl, so we decided instead to transfer our paperwork to a new program that our agency had just begun in Nepal. In hindsight, that was a very bad decision.

The orphanage director working with our agency quickly matched us with an infant girl, and pictures of her found their way onto the fridge, on our office desks, and into our hearts. We couldn’t wait for the Nepalese government to give us permission to fly to Kathmandu to meet her and bring her home.

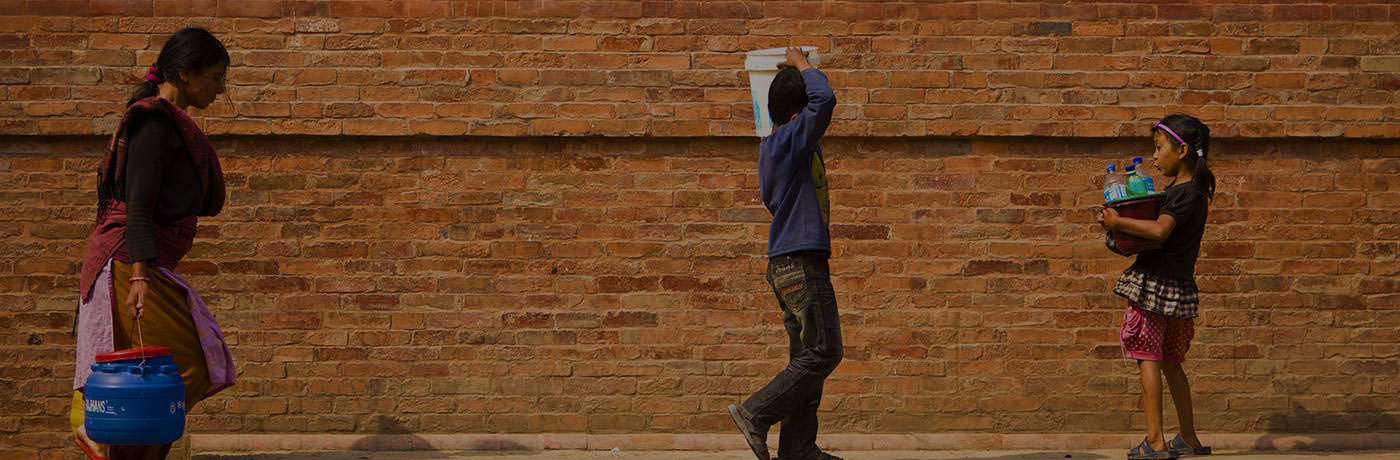

Instead, the government shut down all adoptions in order to investigate the problem of child trafficking (which continues to be a problem) and to completely overhaul its adoption laws. While we waited for that to happen, we learned as much as we could about Nepal, and especially its orphanages, which had already been struggling and were now — with adoptions suspended — having to support their children without the income of fees from successful adoptions. We could see that the children in our orphanage were mostly healthy and happy, cared for by kind, hardworking people. But some reports about living conditions, like this one about orange drinking water, vexed us. The infant slowly grew into a toddler. We waited for over two years. Watched and waited.

Then two bad things happened. The new adoption laws clearly made our match illegal, and we were forced to give it up. In one of the last pictures of “our” little girl, she is sitting in the lap of a caregiver, who is pointing to a large picture of us and teaching her to say “mommy” and “daddy.” But we had to take that picture down and wait to be re-matched. We don’t know what happened to that girl.

The situation of Nepalese orphans now became even more acute for us, because nearly any orphan in Nepal could now turn out to be our son or daughter. (And as painful as the waiting was, that is not an entirely bad way to see the world.)

The second bad thing to happen, however, was the overthrow of the Nepalese government, one of the last remaining monarchies on earth, and its slow rebuilding. Again we waited, eventually opening a domestic adoption concurrently with the one in Nepal, and ultimately deciding to back out of Nepal entirely.

Then the good thing happened. Only five hours after I contacted our agency to close our Nepal file, the agency contacted Susanna to tell us that Liam’s birth mom had chosen us to be his parents. After four years of waiting, everything seemed to happen in five hours. And the whole hard story disappeared entirely in my first moments with Liam. Nothing else was.

Liam is now three years old, which makes me three years old as a father. And despite the delirium of joy with which he first landed in my arms, the more I grow into my responsibilities as Liam’s dad, the more I think about orphans in places like Nepal. It would be intolerable to me if my son could not have healthy food and clean water — at a bare minimum. What about those thousands of other children — who could just as easily have been our sons or daughters — who can barely get a glass of good water?

Donne was wrong. Something else is.

I have come to see our years of waiting as a bitter gift, and even a bitter gift can be put to good use. One of Anton Chekhov’s characters says that at the door of every happy man, there should be an unhappy man with a hammer, constantly tapping, to remind the happy man that there are unhappy people in the world. We do not have a man with a hammer. We have the memory of a little girl learning to say “mommy” and “daddy”; we have the faces of children who might have been our own. We cannot give them a home, or a college education, or many of the advantages we can give Liam.

But giving them clean water seems like a clear place to start.

First family portrait, taken by Liam’s birth mom.

“I’m your dad!”

Chad Engbers and Liam.

Chad Engbers teaches Renaissance and Russian literature at Calvin College in Grand Rapids, Michigan. His hobbies include running, playing guitar and mandolin, and losing at chess. He and his wife, Susanna, adopted their son Liam in 2010.