Articles and information about Splash and the work we do.

August 29, 2014

Don’t Drink the O.J.

Originally published in 2013

It sounds like something out of Willy Wonka: when you turn on the water at a public school in Kathmandu, Nepal, orange juice comes out.

But it’s not the tasty kind with all the vitamin C. “Orange juice” is the (darkly humorous) Nepali term for the city water in Kathmandu, notorious for its high iron content, which turns the water a rusty orange color.

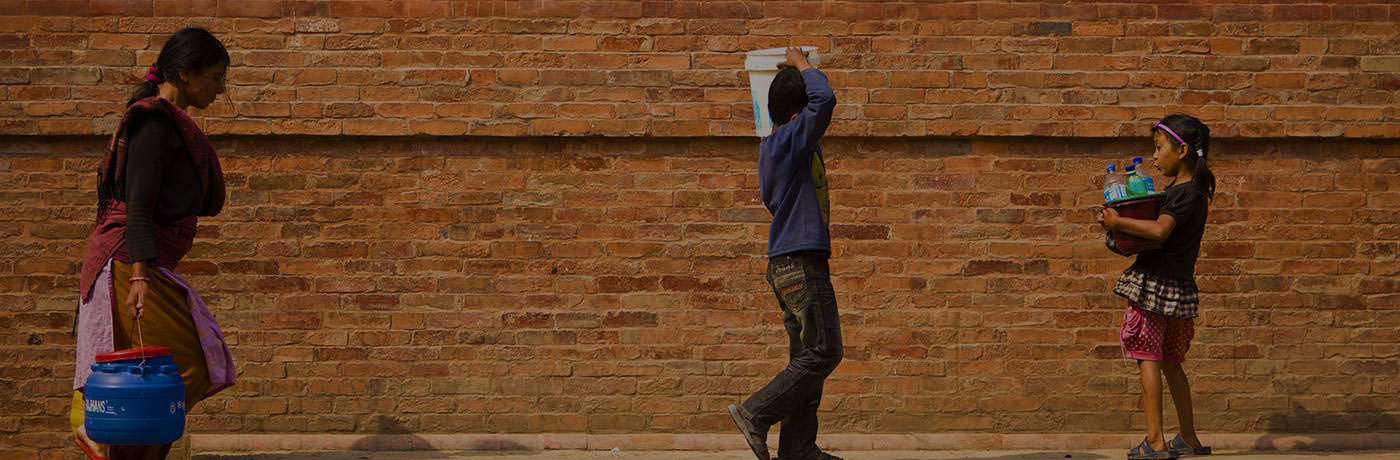

That’s not the only problem with the water in this densely populated urban area (by conservative estimates, close to six times the density of New York City). Like many rapidly growing cities in developing countries, Kathmandu lacks the infrastructure to provide clean, safe drinking water to its residents. Some 10 million children in Nepal suffer from diarrheal disease every year.

When asked to describe the water challenges in Kathmandu Valley, Splash Nepal’s Country Director, Prakash Sharma, doesn’t have to think about it. Two things, he says immediately: water access and water safety.

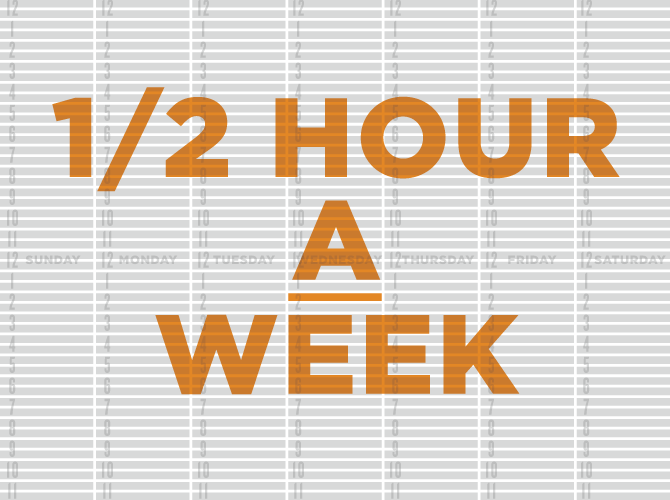

“The bitter truth is that the municipality supplies water for only half an hour every week, and even less in the dry season. People in urban areas must have their own, in-house source of water, whether it’s from a bore well, a hand-dug well, or tanker purchase [all of which cost money]. So access to water itself is a big challenge for poor city children and their families.”

Even if they have water in their homes, says Prakash, water safety is still a challenge, and an even harder one to solve than water access. “The infrastructure in Nepal’s cities is very poor. Water is contaminated because of bad sewage management and pipe leakage. Half an hour of municipal water a week is not enough for a school, so many have wells or make tanker purchases. And in 90% or more of these cases the raw water is ‘orange juice.’”

Prakash says that readily available treatment options, like sand filters, are inadequate. In water quality testing conducted by Prakash’s team in Kathmandu’s public schools, they consistently find high levels of total coliform well above what is considered safe to drink — even in water that is treated and looks clear to the naked eye.

“This [clear but unsafe water] is an even greater threat to kids than the orange juice,” says Prakash. He explains that kids drink more of it, assuming that because it is clear it is safe. “Children,” says Prakash, “especially those from poor and marginalized families who go to government schools, are at high risk of consuming unsafe water.”

The disturbing irony is that schools like these in poor, urban areas, are generally thought to have “access” to water — even though it is unsafe for drinking. Some 99% of charitable water programs focus on providing first-time water access to rural communities. Those efforts are good and well, but they leave gaps (like “orange juice”, E. Coli, and more). The good news is that Splash is filling this gap. Focused solely on vulnerable children in urban areas, Splash is committed to installing and maintaining water purification systems — high-volume systems that clean water to the highest possible standard, removing 99.999% of all biological contaminants — in every public school in Kathmandu. Splash’s team in Nepal, led by Prakash, is already 15% of the way there.