Articles and information about Splash and the work we do.

March 18, 2024

Gender Responsive Assessment Scale: A Conversation with Splash’s Behavior Change Team

Last December, two Splash staff members, Megan Williams and Eskinder Endreas, attended the Global Hygiene Symposium in Singapore. This was the first global gathering specifically focused on hygiene, funded by Reckitt Global Hygiene Institute and Chatham House, and organized by the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine.

The symposium brought together experts from diverse fields, all dedicated to advancing hygiene practices. Discussions revolved around integrating hygiene into various sectors like health, nutrition, and vaccination, aiming to elevate its importance. The event emphasized a shift towards systems strengthening in designing hygiene programs, fostering behavior change, and promoting inclusivity. Crucially, it highlighted the need to address gender disparities in hygiene initiatives, revealing examples of existing programs that were gender exploitative. This prompted a call for reevaluation and inclusion of diverse perspectives. The symposium also underscored the importance of bridging knowledge gaps to facilitate sustained improvements in hygiene practices. It served as a milestone in advancing understanding of hygiene research, policy formulation, and program design, advocating for a holistic and inclusive approach to hygiene promotion.

Arundati Muralidharan, Co-founder of Menstrual Health Alliance India and Coordinator for the Global Menstrual Collective, led a session on advancing gender and social inclusion. One key takeaway was the discussion on a successful hygiene campaign in India, which she found inadvertently reinforced negative gender norms that mothers carry the sole responsibility of caretaking by exclusively targeting mothers and excluding fathers. This highlighted the importance of ensuring that hygiene campaigns are inclusive and do not perpetuate harmful gender stereotypes.

For Splash, examining our curriculum to identify and address any perpetuation of negative gender norms, while striving to advance positive gender norms, will be critical for future program development.

We dug in to this topic with two Splash staff members, Megan Williams (Director of Behavior Change) and Emily Cruz (Senior Global Lead, Menstrual Health), interviewed by Lily Young (Senior Marketing and Communications Manager).

Megan Williams (MW): Arundati Muralidharan primarily led this session, talking about how interventions play a role in gender equity when it comes to hygiene. She gave definitions of the gender equity scale: Is your program negative or harmful towards gender equity? Is it neutral? Is it sensitive, responsive, or transformative?

She gave several examples of different program designs and where they fell on that scale. What was really eye-opening to me personally were some of her references to hygiene programs which were known as successful across the sector. The best example that she gave was a program in India. It used behavior centered design, which is the same methodology that we use, and had extensive community engagement in the design process.

They ended up designing a program that had really positive results. There was a 33% increase in hand washing rates, and that even went into their two-year post evaluation.

But when she looked at the program through a gender equity lens, she said it was actually negative and harmful towards gender equity. That was because the entire program was based on key motivators of mothers. The design of the program was trying to have mothers encourage their kids to wash their hands, so their children would have potential in life and progress in society. For example, in the film they made, the son becomes a doctor. The messaging of the film connects handwashing with the son’s ability to grow and thrive.

The whole campaign only focused on mothers and their nurture. What Arundati described is perpetuating a societal norm that mothers are the primary caretakers of children, and that puts the burden of child rearing on the mothers, which is potentially limiting their own opportunities.

It was such an eye-opener to me. And one of the things that we talked about is that there might come situations where we have to compromise on certain results. For this example in particular, had they just included fathers as a part of that equation all the way through, it might have still been just as effective without perpetuating a negative gender norm. But there could be situations in the future where you may have to compromise results to ensure gender equity.

Now, that might not be the case. Maybe we can't always find a solution that is transformative, but even if we can at least make sure that it's not harmful, that's a good start.

This conversation was really provocative to me to think about each of our programs and ask, “are there programs where we are continuing a norm, or where we're actually being responsive, or trying to push the boundaries and be transformative?"

Lily Young (LY): How would you weigh the impact of a program if it was in conflict with gender equity? For instance, if the impact was lessened and it wasn’t as transformative a program, but the gender equity was greater, how do you weigh that trade off, if there is one?

MW: I don't have the answers to that, and we talked about that directly in conversations at the conference and nobody had an answer. But I think you can always try to design a program that is not going to be harmful and then go from there. Because you can't push the boundaries too far, too fast. You have to balance that a little bit.

LY: These are gender norms in a given society, so how do you design a program that is effective based in that reality? So much goes into designing a program where you have to ask, what messaging resonates with who and who is most likely to push this change forward? And if the answer to that is mothers, then how do you push forward in a gender-equity lens?

MW: It's interesting, because in the example from before, if all their messaging had targeted both mothers and fathers, even just optically, it would not perpetuate harmful gender stereotypes, even if mothers are generally the ones who respond to it.

There is a difference there: you're being gender sensitive. You might not be transformative. You might not be moving the needle on getting fathers to be more involved. But you are recognizing and being sensitive to a harmful norm.

Emily Cruz (EC): I think optically, Megan, like you were saying, if we included male and female representations of a gendered role, for instance in our depictions of janitors, we could show both a male janitor and a female janitor. In the mother's program in Ethiopia (we call it the parent engagement program globally), all of the depictions are of a mother, the front cover of the program is a mother holding her daughter.

If we instead depicted a family, showing a mom and a dad as supportive roles for the daughter, the parent program might not be gender transformative, but it would definitely be gender sensitive. How things are depicted can be so subliminal. The younger generation can see these materials and think that being a male janitor, for example, is not outside the norm.

MW: Even if it's not happening yet, you are helping to normalize things.

LY: You mentioned the parent engagement program. Have you thought about any aspects of our programs that we might be able to make changes to? Or ones we think are doing well or ones where there's room for improvement?

EC: Yes. I want to go through with a fine-tooth comb to pull out all the ways we need to shift our verbiage or the images and the animations in the films. I’m also specifically thinking of the boys’ program. We did human-centered design and the boys choose the name of the program and they voted to have it called “We Can Be Heroes” because they really identified with this motivator of being a hero or being a role model or being a “rescuer” of their female peers, the stronger force. But why do girls need a hero? They can be their own hero. I think that that is potentially harmful because it's perpetuating this belief that boys are always stronger and that girls will always need to rely on them and have them as their heroes, especially for something so personal, such as accepting yourself through the experience of puberty.

That one is the top of the priority list to change, and we need to pick a new name for the program. Also, the mother's program—I want to have an organization-wide discussion around not calling it that anymore, changing the graphics to depict supportive parents rather than just mothers.

So, quite a few things to change and improve upon.

You were talking about sacrificing impact to include this gender lens, and in this case, we're also sacrificing some of our core design ethos. In my example from before, the boys chose the name for the boys’ program, but in reality, from our perspective, it's not transformative, it's not sensitive, it's actually harmful. It's our responsibility with that bird's eye lens to nudge them in a different direction and educate them on these gender norms, even though that's what they chose.

It’s hard, because there is a constant negotiation between being gender sensitive and gender transformative, but also being culturally specific and having things be culturally bound. You also don't want something to be so far on the spectrum that they can't relate to it anymore.

LY: That's the whole point of public health messaging too, you have to be able to reach different people and you’re not going to be able to use the same messaging and motivators for everyone.

MW: That's where I think you balance impact and using common sense judgment. Changing the name of the program probably won't have a negative impact on our results, but the name of it will no longer perpetuate a harmful gender norm, so that seems to me a very easy thing that we can change, and we can still engage boys in renaming it. One of the things that Emily and I were chatting about was, what would it have looked like if we engaged boys and girls in that conversation about the name to begin with, rather than just boys?

Would a girl speak up to say, “no, I don't want you to be my hero”? What would that be like for boys to hear something like, “we want you to be our allies, to be a supportive peer, but not to be our hero”? I think that being able to facilitate those conversations is also a growth opportunity for those boys to learn, what does this mean, and why are we even engaging you in these conversations?

There might be harder programming decisions down the road where applying a gender equity lens could be in direct conflict with delivering our programs. For example, we want to provide girls with autonomy of decision around their bodies, of using tampons and cups, but governments, schools, and parents have all rejected that, and no insertables are allowed in any of our curriculum, and that’s something we have to listen to in order to keep providing our programs.

EC: You have to have a gut check of knowing your audience to make sure you’re not making material unrelatable for them, so that they understand what we’re saying.

There are so many components of gender that we weigh when we are working in different cultures. How do we accommodate that while also still being at least gender sensitive?

MW: Yes, and gently pushing the needle forward.

EC: The design is part of the intervention and the design process is part of the intervention, like how Megan was saying, engaging boys and girls and choosing the program name.

LY: Have you heard any feedback or comments from any of the students or teachers or staff members, anybody pushing back? Have any girls said, “we don't want you to be our hero”?

EC: I haven't heard anything. I will say that the translation of “we can be heroes” in Amharic has less of a power imbalance connotation, so that is comforting, and there hasn't been a ton of feedback in that regard. There have been some comments of wanting boys to participate more.

In one of the sessions, in Abeba’s World, our core menstrual health curriculum, there have been comments wanting boys to participate before Menstrual Hygiene Day. Then, they know more about the topic. If they're part of the organizing committee for Menstrual Hygiene Day, then they should take that course first so that they can be more knowledgeable as they're speaking to the student population.

LY: What’s our status as an organization on making these changes? How are we going to take this information forward and incorporate changes?

EC: It's a priority. It's an undercurrent priority that isn't specifically named, but because the program is designed and we're at this moment of thinking about expansion geographies, it is an opportunity to revisit, as we're contextualizing for a new country, that we can integrate these tweaks as well, at the same time.

It's definitely on our minds, as we adapt our materials.

Related Articles

January 9, 2024

Driving Behavior Change Through Human-Centered Design Approaches

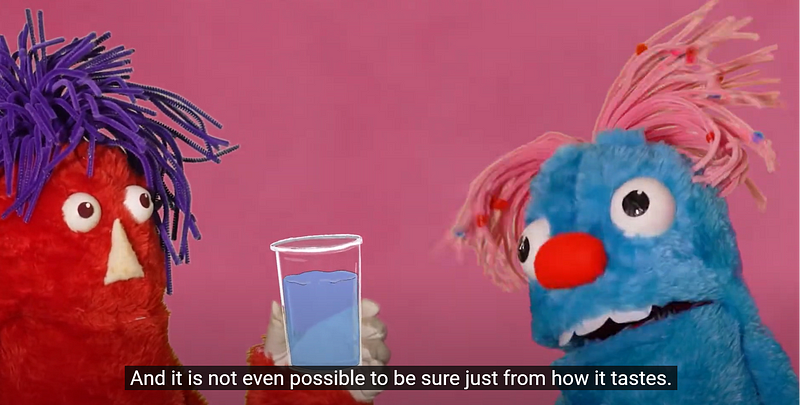

As digital communications become more commonplace worldwide, we set out to create video content for kids about topics like safe water, hygiene, menstrual health, and advocacy.

Read More